A walk down Church Lane in Lymington reveals a fine brick wavy wall on the right hand side while, on the opposite side, a little further down is another which is rather less sophisticated but still impressive. It is worth remarking that that they were built about 150 years apart. Such walls are relatively unusual and it is curious that there are so many in Lymington. I think we should first of all try to clear up the matter of the various names for such walls and I turn first to one of our leading authorities on the history of brickwork in England, namely, the late Dr Ronald Brunskill (1929-2015). In his masterly book, ‘English Brickwork’ (1977) he states:

The continuously curving or serpentine garden wall, sometimes known as a crinkle-crankle, was especially popular in Suffolk in the later Georgian period for the cultivation of slightly tender fruits such as peaches and nectarines. Some of these walls are delightful. The best known, several hundred yards long, abuts on to the main road between Wickham Market and Framlingham. (pages 28-9)

And in the glossary of this book, compiled in association with Alec Clifton-Taylor, it states:

Crinkle-crankle wall: a garden wall which was usually only half a brick in thickness but which gained stability from serpentine curves on plan. Such walls are found mainly in East Anglia where they helped provide some protection against the winds for the more delicate fruits such as peaches and nectarines. (page 78)

A footnote in Clifton-Taylor’s magisterial study entitled, ‘The Pattern of English Building’ (3rd edition 1972), it is stated that “The continuously curving or serpentine wall was a speciality of Suffolk…According to Norman Scarfe there are forty-five of these walls, mostly late Georgian, in Suffolk alone and perhaps no more than twenty-six in all the other English counties.” (note on page 250)

So Lymington should be more than satisfied to have about eight to which, perhaps, we should add the two at Everton Grange.

I feel I should clear up a technical point regarding these walls being described as being ‘half a brick’ thick. By the opening of the eighteenth century the traditional English brick size is very proportional measuring 9 inches long, 4½ inches wide and three inches deep so a brick thick would equate to the long side while the short side (4½ inches) would be half a brick. So walls built with bricks laid lengthways are half a brick thick.

A simple demonstration

Now I am going to suggest a bit of homework: from the copious junk mail you undoubtedly receive regularly take an unwanted sheet of A4 paper, fold it half longwise, and cut along the fold, then fold either piece (or if your excited by the idea, why not both?) in half and then half again so you have a zigzag or crinkle. This you can place upright on the table and you will see that it is stable. Even if you gently blow it (you might not want any other adults to see you doing this!) you will find it may skid along the table but it will not easily fall over. This simple experiment immediately shows how the crinkles or zigzags impart stability; a principle that applies to the real life walls which require no buttresses or other supports.

The origins of Lymington’s wavy walls

Elm Grove wall, the finest of the historic serpentine walls, probably built about 1800

In 1991 the Lymington Society published ‘Occasional Paper, No. 2’ on this subject written by J.C. Taylor. In this he states, that the wall in Church Lane, a boundary between the lane and the garden of Elm Grove House, “was built in 1798 by the commander of the garrison troops based in Lymington to defend it from the French.” My extensive and detailed search through the literature and records of that time reveals nothing to substantiate this though the threat of invasion was real enough. It is not easy to imagine what defensive advantages a crinkle-crankle wall would bestow as opposed to a straight wall. Later he remarks that one of the first tasks of the Hanoverian commander, “was to build a wall to screen their activities from the disapproving eyes of the townsfolk and so the wavy wall, a type of construction common in northern Germany, came to Lymington.” This raises the further question as to why a wavy wall would make a better screen than a straight wall. And why are the eyes of the townsfolk disapproving—what were those soldiers up to?

After describing the supposed benefits of such a wall he continues, “Not slow to recognise a good thing when they saw one, the locals embarked on a spate of similar wall construction. The catalyst for such activity was the ready availability of cheap labour in the shape of the French prisoners of war.” A little later he makes the extremely dubious comment, “As a consequence there are more wavy walls to be found in Hampshire and the Isle of Wight than in any other part of the country.”

He does describe the very fine wavy wall in the garden of Everton Grange: interestingly, Marion Cran in her book, ‘I know a Garden’ published by Herbert Jenkins in 1933; writes of the occasion when she visited the then owners, Col. William and Mrs Kemmis at Everton, she asked, “What made you come here?” to which she received the response, “The ‘bendy’ walls and that big oak.” It is informative to read the author’s further observations, “The kitchen gardens and greenhouses are behind huge walls (meaning hedges) of ancient yews, topped with peacocks and further more enriched within by the quaint bendy walls which are supposed to have been built by French prisoners in the Napoleonic Wars (there are walls like it in one place in Virginia, America). They are of narrow bricks one brick thick (sic), in long wavy line of continuous, semi-circular bays.” (page 138).

Dennis Wheatley’s descriptions

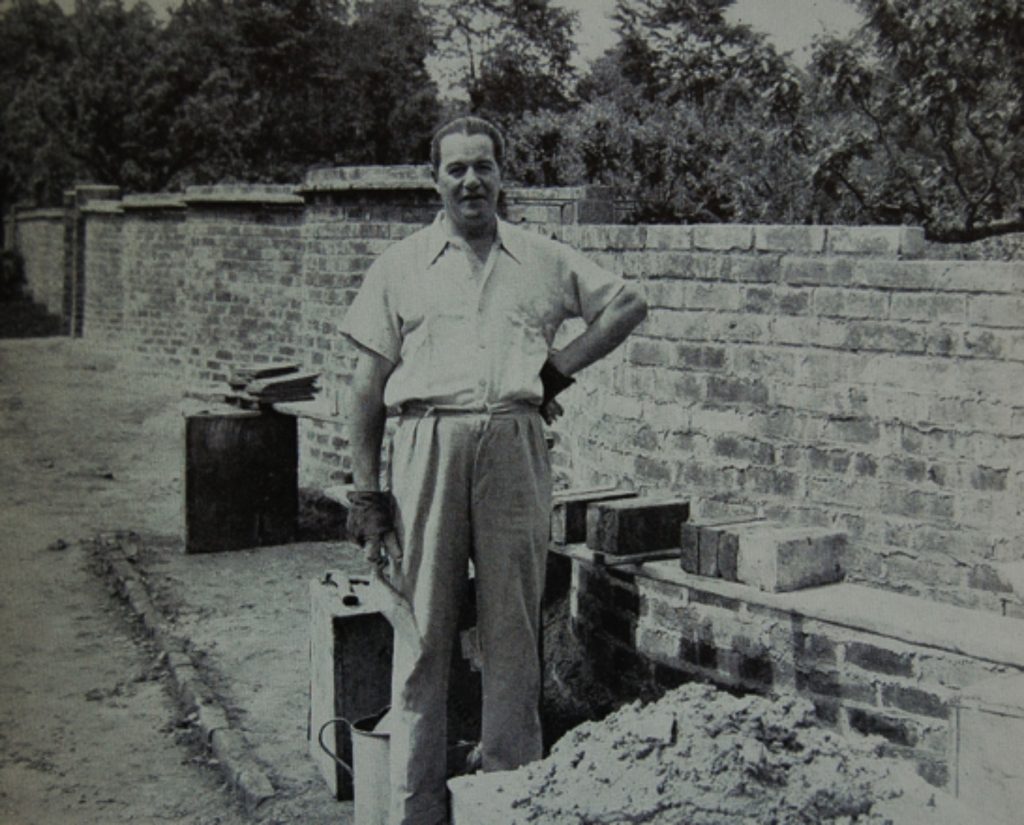

The wavy wall designed and built by the author and novelist Dennis Wheatley, late 1940s

The renowned novelist, Dennis Wheatley, was an amateur but skilful bricklayer and, after purchasing Grove House (Grove Place when he bought it in 1945), began to practise and refine his skills. He left a record of his achievements in a semi-autobiographical work called, ‘Saturdays with Bricks’ published in 1961.

On page 95 he writes, “It was the French prisoners-of-war in Napoleon’s time who introduced serpentine walls into England. Following their capture, they were shipped to Portsmouth, then confined in the Isle of Wight. After a time, some humanitarian suggested that they should be allowed out on ticket-of-leave to work in gardens. That is why there are many more serpentine walls in the Isle of Wight and South Hampshire than in any other part of the country. They are said to have originated in Brittany, and it is highly probable that the Frenchman who first thought of making a wall wavy was not inspired by any artistic motive, but by economy.”

Unfortunately, the author gives no source of reference for these statements, so they have no independent historical authority but, nevertheless, require quoting (even if dubious) as a possible explanation.

The crinkle-crankle wall just below and opposite that of Elm Grove House was built by Dennis Wheatley and remains as a very tangible record of his bricklaying skills.

The walls are listed as Grade II

In its List of Buildings of Special Architectural or Historic Interest for Lymington the Department of the Environment, 28 October 1974, records two walls, namely: ‘Garden wall to Elm Grove House’:

‘C18. Red brick crinkle-crankle garden wall to south of house’, Grade II, and in the rear garden of No. 73 High Street: ‘C18. Crinkle-crankle 6 ft high wall of coped red brick with some grey headers’, also Grade II, both are recorded as having group value. (pp. 32 and 62)

Edward King (1821-85) in his Old Times Revisited, first published in 1879, makes only a solitary reference of these walls, “The last house in Church Lane on the west (Elm Grove House), and the garden where the serpentine wall is…” It seems evident that he did not consider them of sufficient merit or general interest to warrant a fuller description or explanation. This is a pity but his grandson, also Edward King (1893-1974), is a little more expansive in describing this wall. In his book, A Walk through Lymington, first published in 1972, he states that Elm Grove House has, “an elegant curved garden wall. It is not well known that there are several walls like this (but not so good) behind the shops in the town; they are reputed to have been introduced by the French during the revolution.” (p.7)

A factual account of 1813

We have to turn to Charles Vancouver, whose book General View of the Agriculture in Hampshire was published in 1813, to provide a contemporary account which, possibly, may refer to the Elm Grove House garden wall. I think it probably does.

The expense which Mr. St. Barbe, near Lymington, has incurred in building a very neat red brick wall of a waving character, and with a divergency only of 11 inches on a base of 22 feet, carried half a brick thick to the height of six feet and a half above the foundation, which latter is formed of a nine-inch wall, and 18 inches high, amounts, on a wall 75 yards in length, to about £50. (including materials and workmanship in that neighbourhood), equal to about £3 12s. per perch, running, but not reduced measure, and which expense also includes the piers at the doors and gates-way, which are four, built two feet and an half square, and to the height of the wall, six feet and an half, as before-mentioned. In other cases, garden-walls are projected on the principle of a running right-angled triangle; that is to say, on the centre of a base of 20 feet, a perpendicular or departure is set off, of 10 feet to every angular point of the wall, which is then built straight from the end of the base line to that of the perpendicular, in length about 15 feet, and thus ranging at right angles with each other, the whole length of the wall (see illustration). [p.287, “Gardens and Orchards.”]

These walls are such a distinctive architectural feature in Lymington that it seemed worth drawing them to the attention of readers of the ‘A&T’ and showing how they have exercised the minds of earlier commentators. I am sure many will feel, as I do, that they are curiosities with architectural and artistic merit.

I have drawn attention to various descriptions of these walls not to find fault with those supplying the descriptions but to indicate the lack of reliable historical evidence, some of which is quite contradictory. I hope, therefore, that my observations, research and conclusions provide a clearer understanding and appreciation of the subject.

This article was written by the President of the LDHS Jude James. We are grateful to him for allowing us to use publish it on our website. It should be noted that this was first published in the New Milton Advertiser and Lymington Times on 28th May 2016.